Indice - Table of contents

New Stuff[hide]

Musicos: Rafael Paseiro Monzón

Musicos: Dennis Nicles Cobas

Musicos: Jiovanni Cofiño Sánchez

Musicos: Yasser Morejón Pino

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich : 2024 Monterey Jazz, P...

Resenas: Vacilón Santiaguero (Circle 9 ...

Staff: Bill Tilford

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich : 2024 Monterey Jazz, P...

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich : 2024 Monterey Jazz Fe...

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich : testing 123

Grupos: Pupy y los que S... : Discography - 1995- F...

Reportes: From The St... : Cubadisco 2...

Reportes: From The St... : Jazz Plaza ...

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich : Irakere 50th Annivers...

Photos of the Day [hide]

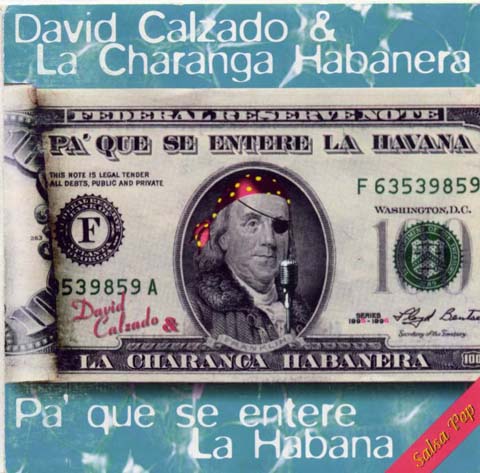

SpanishEnglishDiscography - Pa' que se entere La Habana

listen & purchase

1995 - Pa' que se entere La Habana

By 1995 Charanga Habanera and their second album, Hey You Loca, had become a major sensation in Havana. Their concerts were packed with young "Charangueros" who danced and dressed as they did and knew all of their songs, each of which became, in rapid succession, a huge radio hit. With the band's popularity reaching "mania" proportions, singer Leo Vera left without warning to join Chucho Valdés' legendary Irakere. Leo had sung half of the band's hits and when he departed, his version of Mi Estrella was the #1 hit in the country. It was a major blow but David Calzado, as he continues to do today, landed on his feet by relying on his uncanny ability to find and quickly mold new talent. To replace the mature and virtuosic Vera, he shocked everyone by choosing a 16-year old boy with a much lower range, forcing Sombrilla to take over most of Leo's songs. That 16-year old turned out to be none other that Michel Maza, who was an immediate success and remains to this day one of the biggest stars in Cuba.

The drastic musical changes brought about by the Timba revolution were accompanied by equally drastic changes to the inner workings of the Havana music scene. Musicians were allowed to earn dollars from their performances and a convoluted quasi-capitalistic economic substructure began to develop. Those with musical talent became highly motivated to become Timba musicians and the fierce competition forced them to higher and higher levels of virtuosity and creativity. Meanwhile a whole industry of "jineteros" grew up around the club scene, with attractive young Cubans of both sexes seeking out foreigners for everything from cigar sales, to "romance based on finance", to outright prostitution. It was the "end of the innocence" for La Habana and La Charanga Habanera and the societal upheaval provided irresistibly fascinating material for lyrics. Following in the footsteps of Juan Formell and Los Van Van, the charangueros became chroniclers of pop culture and language. From their vantage point as the superstars of Timba, they began to write lyrics about the scene and their own role in it. For the first time, the bandmembers themselves wrote the bulk of the songs, rather than applying their innovative arranging ideas to the work of established songwriters Limonta, Piloto and Manolín. The new lyrics used freshly-invented jargon, humor, and heaping doses of double-entendre to paint an irreverent and at times brutally honest portrait of the Havana of the mid-90's. They also began to change their musical ideas, catering to the wild new sexual dancing styles and incorporating a kind of Cuban rap into their coros that drove their crowds to a frenzy. And they did it all brilliantly, with intense musical precision and creativity. "Pa' Que Se Entere La Habana" was a key turning point, with one foot in the bright, euphoric world of Me sube la fiebre and Hey You, Loca and the other striding forcefully towards the dark, powerful and aptly-title Tremendo delirio, the fourth and final album before the band splintered into three pieces in 1997 and 1998.