Archivo

New Stuff[hide]

Musicos: Dennis Nicles Cobas

Fotos: Eli Silva

Grupos: Ritmo Oriental : 1988 - Vol. IX - 30 a...

Musicos: Rafael Paseiro Monzón

Musicos: Jiovanni Cofiño Sánchez

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich : 2024 Monterey Jazz, P...

Resenas: Vacilón Santiaguero (Circle 9 ...

Staff: Bill Tilford

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich : 2024 Monterey Jazz, P...

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich : 2024 Monterey Jazz Fe...

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich : testing 123

Grupos: Pupy y los que S... : Discography - 1995- F...

Reportes: From The St... : Cubadisco 2...

Reportes: From The St... : Jazz Plaza ...

Photos of the Day [hide]

Sin Clave No Hay Na

Timba and The United States, Part II

The Initial Reception of Timba in The United States

La Timba y Los Estados Unidos, Parte II: La Recepción Inicial de la Timba en los E.E.U.U

(Para leer este artículo en español oprima aquí)

If musical merit was the only ingredient necessary for mass popularity in the United States, Timba would have quickly taken the country by storm the same way that the Mambo did years earlier. However, that is not enough, as many Jazz musicians have also learned the hard way over the years. An infrastructure to support the music is also required for any genre to reach large numbers of listeners, and that was not in place for Timba when its sounds first reached the United States. In order to fully understand the reasons for this, we first need to briefly revisit the three decades prior to Timba’s emergence as a distinct style.

In the 1960s, there was no significant ongoing cultural exchange between the United States and Cuba. This does not mean that there was no exchange of ideas of any sort - musicians both here and there were listening to each other by various means, and radio enthusiasts such as this writer were keeping up with what was happening in Cuban music via shortwave stations such as Radio Habana Cuba, Radio Rebelde etc. However, most of the general American public remained unaware of the new directions in which popular music on the island was beginning to move in the late 1960s, and most of the listening audience here instead focused virtually all of its attention on what came to be called “Salsa” in the United States. The term “Salsa” was designed to simplify the “packaging” of various rhythms of both Cuban and Puerto Rican origin, but it does not incorporate the newer musical styles that were developing in Cuba. It was very successful as a marketing tool; so much so that many of the original terms for distinct rhythms faded into the background.

In the 1970s, Timba’s immediate musical ancestors (Songo and the new styles of music described by some writers as Nueva Onda, not to be confused with the more widely-known Nueva Trova movement) became increasingly popular both in Cuba and internationally, and these new and exciting styles were too exciting for many Americans (especially musicians) to ignore. The late 1970s also brought limited cultural exchanges that made it possible for more Americans to be exposed to what was happening on the island. Some American groups even recorded covers of some of the new Cuban music. For example, in New York, Tipica 73 recorded modified versions of Los Van Van, Ritmo Oriental and Reyes 73 songs, and Charlie and Eddie Palmieri recorded some Mozambiques. Some American charangas in both New York and Miami also included some newer Cuban compositions in their repertoires. Most of these bands americanized the rhythms somewhat, and the end result was usually more progressive than regular Salsa but less so than the original Songo or Nueva Onda versions of the songs. For their efforts, these bands also endured some very strident criticism from some American political hardliners who accused them of playing “the enemy’s” music, and the few American radio programs that came into possession of current recordings from Cuba and dared to play them also received their share of hostile mail (there was no email yet) and telephone calls. Ensembles that toured the U.S. from Cuba during this period usually encountered some minor groups of protesters in cities such as New York and Chicago as well as much more numerous and vociferous complaints from exile groups in Miami. All of this had the effect of deterring many musicians and radio stations from publicly embracing the new styles in spite of the fact that most of the younger listeners liked what they heard when they were given an opportunity to taste the new music.

The story of the 1980s is mostly similar to that of the 1970s for the eastern and midwestern United States, with a still small but gradually expanding audience due to the influence of cultural exchanges and those musicians and radio stations who remained willing to confront some hostile political critics for the sake of the music. By this time, however, the marketing machine for “Salsa” was now sufficiently entrenched that it frequently crowded out more progressive forms of the music. Two notable exceptions during this period were in California and Puerto Rico. In California, both Los Angeles and San Francisco developed vibrant scenes with musicians, dancers and listeners that absorbed, performed and danced the latest music coming from Cuban groups such as Los Van Van, Ritmo Oriental and Estrellas Cubanas. In Puerto Rico, groups like the original Zaperoko and Batacumbele both studied with Cuban musicians and played Songo more faithfully than the American bands of the 1970s. There was much less political hostility in these places than in the eastern United States as well.

As Timba appeared as a distinct style in the early 1990s, the cultural exchange activity also increased slightly, and more of the groups in Cuba that played the new music were able to tour the United States, although there were still significant limitations to this activity. With the notable exception of Miami, tours in U.S. cities also experienced significantly fewer and smaller (and in many cases no) political protests. There was also a relatively small but enthusiastic group of Americans (compared to the fan base of Salsa) willing to embrace the new music when it arrived, and a few companies such as Ediciones Vitral, QBAdisc, Bembé and Ahí-Namá arose to help distrubute recordings of Cuban groups to the American market. After three decades, however, there was no longer a significant support structure in place for introducing large numbers of American listeners to modern Cuban music, and this contributed to a more limited growth of Timba’s audience than we might have seen otherwise. A limited number of agents and marketing support people took an active interest in the music during this period, and some of those who did were sufficiently disreputable and/or incompetent to cause serious fiascos in what might otherwise have been successful tours. To complicate matters even further, in Miami in particular, elements of the Cuban American community mounted a largely successful campaign to inhibit appearances by bands from Cuba as well as radio exposure of their music.

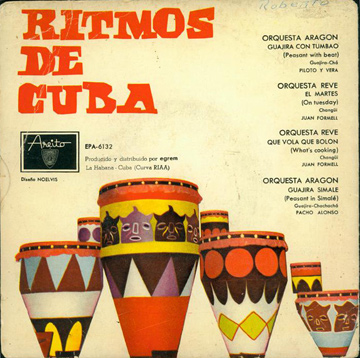

After 2001, the door slammed shut on live tours (with rare exceptions) by most bands from Cuba for most of the decade to follow, and for most Americans, listening to Timba during that decade meant listening to recordings or the very few American bands that were now playing some Timba for small audiences. There was not a total ban on groups from Cuba during this period; for example, this writer saw Orquesta Aragon twice during this decade in Virginia and Ohio. However, the ban was tighter on Timba bands - tight enough to help keep Timba’s fan base much smaller than it might have been. On the bright side, more recordings became available for Americans thanks to third-country labels and distributors in Europe, Canada and Latin America.

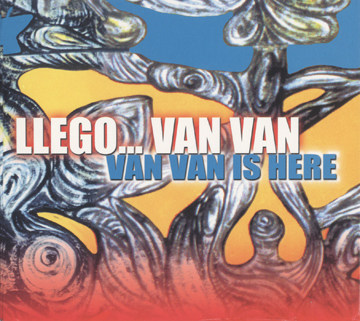

Periodically thoughout these decades, there were occasional recordings of modern Cuban bands tailored to the American market, but these were not always faithful to the music and sometimes suffered accordingly. For example, Columbia Records released two Irakere recordings . The first, Irakere, was a Jazz album that stayed true to the group’s musical vision but was also intense enough that it appealed primarily to Jazz fans. The second, Irakere 2 (1980) was a dance album tailored to American listeners, and it was sufficiently watered down to be one of the weakest items in their discography. Another example: Los Van Van also took two runs at the American market. In 1989, Island Records released Songo, which like the Irakere dance album was sufficiently “softened” to be a disappointment to those who already knew the band. On the other hand, in 1999, Llego Van Van (Atlantic) was true enough to the band’s vision to be popular, stand up well in the discography and even win a Latin Grammy. Finally, Manolin’s Giro Total (SONY 2003) tried to hard to adapt to American listeners and was a commercial and critical failure. The moral of this story is that the recordings that remained true to the music found a niche among American listeners, and those which changed the style to become more marketable usually did not. We’ll say a lot more about this point in future chapters.

As we move to the present, a new generation of listeners tends to keep music and politics separate (as we do here at Timba.com), and Timba now has a significant dedicated following in the United States. However, that listener base could be much larger than it is were it not for the fact that the genre faces many other challenges similar to those faced by other sophisticated forms of music such as jazz. In the articles to come, we will examine each of these in detail. For a much more detailed history of the music itself during the period, see Kevin Moore’s Timbapedia.

Next: Timba and the American Club/Concert Scene