Indice - Table of contents

New Stuff[hide]

Grupos: Ritmo Oriental : 1988 - Vol. IX - 30 a...

Musicos: Rafael Paseiro Monzón

Musicos: Dennis Nicles Cobas

Musicos: Jiovanni Cofiño Sánchez

Musicos: Yasser Morejón Pino

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich : 2024 Monterey Jazz, P...

Resenas: Vacilón Santiaguero (Circle 9 ...

Staff: Bill Tilford

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich : 2024 Monterey Jazz, P...

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich : 2024 Monterey Jazz Fe...

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich : testing 123

Grupos: Pupy y los que S... : Discography - 1995- F...

Reportes: From The St... : Cubadisco 2...

Reportes: From The St... : Jazz Plaza ...

Photos of the Day [hide]

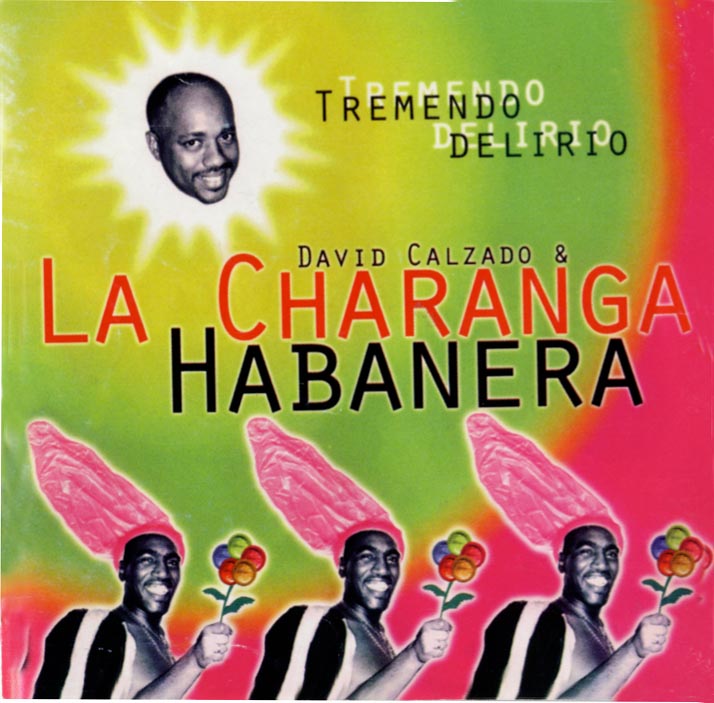

Study - Clave Analysis of Tremendo Delirio

This supplement to the main article on "Tremendo Delirio" assumes that you've already read "A Study of Clave Changes in the Music of Charanga Habanera" and "The Four Great Clave Debates". It also assumes that you're more than just a little bit out of your mind.

The first two Charanga Habanera albums are loaded with clave changes of all types. The third and fourth have relatively few and the fifth, which I've yet to analyze in minute detail, sounds like it may, (with the exception of a section of the homenaje to traditional charanga), be entirely in 2:3 rumba clave. The first question one might ask is "why?", and the answer is probably that neither the simple clave structure of the later albums, nor the mind-bending complexities of the earlier ones was a conscious artistic decision.

It was Juan Formell who coined the term "Clave License". What I got from that legendary interview (In Rebeca Mauleón-Santana's "101 Montunos") is that Cubans don't really think about clave. They feel music a certain way and it's possible to create from their music a theory of "clave" which explains and organizes a great deal of the rhythm section playing. But to the creators, what makes a given musical arrangement work is that it feels right. They never bother to analyze the clave structure -- they just keep "arranging" until the result sounds right to them. They know what good Cuban music sounds like and they know when what they've created sounds like good Cuban music and they make this decision before they even consider what the clave is doing. Of course, it's the composers and arrangers, more than the players who have the luxury of exercising "clave license" subconsciously. Even the top Cuban musicians still have to know, at some conscious level, when to change their patterns. The Cubans, while they may be the last to think about clave, are also the first to get extremely irritated when it gets crossed!

An even more significant revelation from Mr. Formell (undoubtedly the best interview in Timba) is that he attributes his 30+ years of staying on top of the Cuba's Hit Parade primarily to one activity -- he watches the dancers and tries to write music which reflects and anticipates their changing dance styles. As the dancers have evolved, so has his music . This is probably the best explanation for the changes in clave structure in Charanga Habanera's (and Formell's) music. Let's go back a step and review a concept introduced in the earlier articles -- all of CH's cuerpos are played in 2:3 rumba clave. I have yet to find a single exception to this rule. When the bongocero drops his bell and starts his martillo, and the mood changes to the one that whining Timba critics refer to as being overly salsa romantica, the Charanga Habanera timbalero always plays cáscara and 2:3 rumba clave. For the high energy, unabashedly timba sections of the arrangements (the coros, mambos, and breakdowns), the early Charanga Habanera favored, about 70% of the time, 3:2 clave. This is not to say that they didn't have some blazing arrangements like "Te voy a liquidar" which stayed in 2:3 throughout, but in general, when they really wanted to make the dancers work up a sweat, 3:2 was their bread and butter groove. Add to this the fact that Timba bands love to start the arrangement with a taste of the later coro section and it's easy to predict that a series of clave changes will be unavoidable. From the mid-90's on, however, 2:3 clave became the dominant groove for not all, but considerably more than half of Timba, including Charanga Habanera, and the need for clave changes began to subside.

Thus, we can analyze all but three of the tracks on "Tremendo Delirio" as follows: "2:3 rumba clave". That was easy, eh? This leaves "¿Qué quieres de mí?" which is really also 2:3 except for the first 14 seconds, "Hagamos un Chen", and the album's most convoluted track, from a clave perspective, "Charanguéate". Ironically, it's composed by Manolín, whose group has almost no clave variations. If I ever finish with Charanga Habanera, I'll next move to Manolín and do a thorough analysis of his albums, but offhand, I can think of only one Manolín song ("Ella no vale nada") which is in 3:2, and no songs at all which have a clave change. Manolín's music is very reflective of the late 90's trend towards 2:3. It may also have had a strong influence on that trend, but that's a future topic of discussion.